| « Previous | News | Next » |

October 08, 2015

Choose

Your

Sangiovese

Adventure

You can’t talk Italian wine without talking Sangiovese. Versatile, finicky, and capable of ineffable heights, the most planted grape in Italy is also one of the world’s most important. Long gone are the days when vapid wicker-bottled Chiantis are the norm. Sangiovese is reigning strong, and its four most important appellations show just how responsive to terroir this grape is.

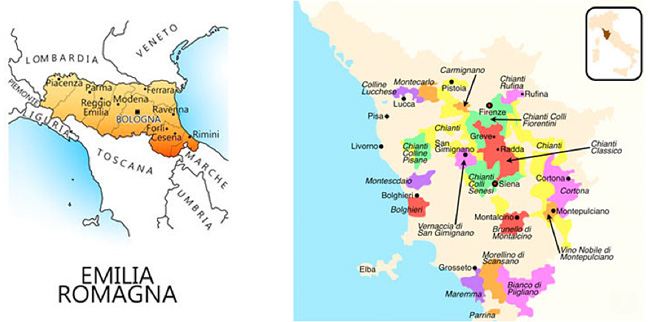

Emilia Romagna: Ripe and Juicy

Bologna, in the heart of Emilia Romagna, is the most porticoed city in the world, meaning that there are miles and miles of covered walkways that wind through this medieval town. Meaning, when you see a little osteria (hopefully it’ll be this one), you already feel like you’re halfway inside, so you might as well go in. When you are inside, what more could you want than a bone-warming plate of tagliatelle al ragu—one of the region’s specialties—and a glass of wine? In your glass, you might find Lambrusco, the local red fizzy that serves as a fun counterpoint to the region’s rich cuisine. But if you’re lucky, it could be a glass of Giovanna Madonia’s Sangiovese di Romagna.

Bologna, in the heart of Emilia Romagna, is the most porticoed city in the world, meaning that there are miles and miles of covered walkways that wind through this medieval town. Meaning, when you see a little osteria (hopefully it’ll be this one), you already feel like you’re halfway inside, so you might as well go in. When you are inside, what more could you want than a bone-warming plate of tagliatelle al ragu—one of the region’s specialties—and a glass of wine? In your glass, you might find Lambrusco, the local red fizzy that serves as a fun counterpoint to the region’s rich cuisine. But if you’re lucky, it could be a glass of Giovanna Madonia’s Sangiovese di Romagna.

Giovanna Madonia grows her grapes about an hour south of the city in a town called Bertinoro, located in the eastern foothills of the Apennines—a mountain range that runs down the spine of Italy. Though Tuscany (which lies just on the other side of the Apennines) has become synonymous with Sangiovese, Emilia Romagna is well-suited to this grape, producing a version that is generally plumper, rounder, and juicier than its Tuscan cousin. In fact: “It is possible, according to some researchers, that the beloved Sangiovese grape of Tuscany actually cropped up first somewhere in Romagna” (Joseph Bastianich and David Lynch, Vino Italiano). This is still up for debate, but it’s clearly a happy grape on either side of the Apennines.

The Madonia estate was cultivated by her grandfather and father, who was the first president of the Consortium of Wines of Romagna. Her grapes are grown only 5 miles from the Adriatic Sea. The 2011 ‘Fermavento’ is 100 percent Sangiovese from calcareous-clay soil (good for water retention, drainage, high acidity) with southwestern exposure. The nose shows currants, black cherries, baking spice, tobacco and tea leaf on a bright, friendly palate. It has a smooth, velvety texture, with hints of licorice on the finish. It’s lively, with an underlying deep succulence that will keep you returning to the glass. This was even better on day two.

The Madonia estate was cultivated by her grandfather and father, who was the first president of the Consortium of Wines of Romagna. Her grapes are grown only 5 miles from the Adriatic Sea. The 2011 ‘Fermavento’ is 100 percent Sangiovese from calcareous-clay soil (good for water retention, drainage, high acidity) with southwestern exposure. The nose shows currants, black cherries, baking spice, tobacco and tea leaf on a bright, friendly palate. It has a smooth, velvety texture, with hints of licorice on the finish. It’s lively, with an underlying deep succulence that will keep you returning to the glass. This was even better on day two.

Chianti Classico: Buns of Steel

After decades of lackluster exports, Chianti’s international reputation during the mid-twentieth century was floundering. From Guildsomm.com: “Historically bottled in a fiasco due to the inferior quality of Italian glass, the squat, straw-covered Chianti bottles came to epitomize the rustic, cheap nature of Italian wine in the late 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s.” Things started to change when the Antinori family introduced the world’s first Super Tuscan in 1971, eschewing the DOC system and reminding international drinkers of the quality Chianti terroir was capable of. At the same time, this move to ignore the DOC system’s blending requirements underlined the need to fundamentally re-examine DOC specifications. In 1984, Chianti and Chianti Classico were upgraded to DOCG status, and the blending formula was changed so that only 2 percent white grapes were allowed (as opposed to the previous 30). They also placed higher restrictions on yields. Meanwhile, Chianti winemakers got serious about quality, using temperature-controlled fermentation in stainless steel tanks; aging in smaller, cleaner oak barrels; and exposing the grapes to longer skin contact. The second half of the century was golden for this famous hillside region.

This is when Paolo de Marchi came on the scene. De Marchi is a Piemontese who has created one of the most important small estates in Chianti Classico. His family purchased the Isole e Olena estate in the fifties, but Paolo took over in 1976. He experimented with international varietals, which was important as Chianti underwent its identity crisis. He ultimately decided the region’s best hope was in its hometown varietal, Sangiovese. In 1980 he created a 100 percent Sangiovese that set the standard for the pure Sangiovese movement in Chianti. His small winery soon became ranked with the major players in the metamorphosis of this important region and remains so today. As Antonio Galloni put it: “Paolo De Marchi remains one of the most forward-thinking producers in Italy. His 100% Sangiovese ‘Cepparello’ was a ground -breaking wine in the 1980s, when Sangiovese was a four-letter word and international varieties were all the rage. Now the Gran Selezione is hot and there has never been more focus on pure Sangiovese in Chianti Classico… Make no mistake about it, these are some of the greatest wines being made anywhere in the world.” (09/2015)

De Marchi’s wines simply hit it out of the ballpark. His 2012 Isole e Olena Chianti Classico has an alluring concentration, with notes of violet, chocolate-covered cherry, red fruit, leather, cassis, cherry liqueur, and cigar box. The rich velour texture gives way to integrated tannins while maintaining the nervy acidity that Chianti is famous for. Ending on a silky, sensual note, this is ridiculously easy to drink. This has the structure to stand up to big meat, so pair with Seared Steak and Potatoes.

Montalcino: Brawn and Brains

About 25 miles separate Chianti from Montalcino, but the climate shifts significantly: Montalcino is dry, hot, and more Mediterranean—and gets even hotter as you move south. Though altitudes are similar to Chianti, the soil has more limestone and sand, which tends to speed up ripening. In fact, Montalcino experiences much earlier harvests than other Sangiovese zones, often finishing by the end of September. And the wines are notoriously intense: layered, tannic, ultra-age-worthy, and the quality is going nowhere but up. Some attribute the wine’s concentration to the Brunello clone itself, though that theory has been a subject of debate lately.

Mastrojanni has gained a reputation in the region for stylish, traditional wines. Andrea Machetti has been involved with the Mastrojanni estate since 1992. Known for his propensity toward tradition, he has been adamant about not introducing barriques to the cellar, which would impart a more pronounced oak flavor. Rather, he believes in the larger, more traditional botti. The winery is located in Castelnuove dell’Abate, a subzone in southern Montalcino known for Brunellos that achieve elegance and power. The vineyards receive ample sun, plus a cooling effect from the Orcia River, and are protected from extreme maritime breezes by the Montalcino ridge. Their soils are rich in gravel and clay, which retain water, and limestone and sandstone, which retain heat. Many of their vines are over 35 years old.

The 2013 Rosso di Montalcino has a raw silk texture, with aromatics of red fruits, sour cherry, tea leaves, and dusty rose. It’s streamlined and tense, with clear tannins but a graceful touch. The Conzorzio del Vino of Brunello di Montalcino awarded this vintage 4 stars (2010 received 5, but that’s been hailed as a “once in a lifetime” vintage).

Vino Nobile di Montepulciano: Blurring Boundaries

Further inland, about 20 miles east of Montalcino, you’ll find Montepulciano, a quiet hilltop town and another Sangiovese stalwart. Though the smallest of the Tuscan DOCGs, it has a long tradition, and in 2010 fought hard to maintain the “Nobile” part of its name, which has been used since the 1920s. The climate here is more seasonal and continental—more mild in general. The tannins tend to be softer than Brunello and the acid less intense than in Chianti Classicos, meaning they are generally ready for earlier drinking—though the quality can vary radically from vintage to vintage. According to Vino Italiano, “The slopes of Montepulciano are more open and gently rolling than tight steep pitches of Chianti Classico or Montalcino (allowing in more sunlight), and the soils are generally sandier and more alluvial (advancing ripening), yet the elevations are the same.”

The della Seta Ferrari Corbelli family has owned the estate since the mid-20th century. The 2011 Vino Nobile di Montepulciano (with 10 percent Merlot) has an alluring, earthy nose that hints at forest floor, spice, and violets. It’s medium-bodied and fruity but has good, grippy tannins. Gives way to juicy cranberry on the palate. This is a bright, playful wine with an underlying complexity.